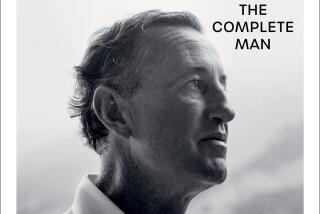

Spymaster ‘Intrepid’ Dies at 93

- Share via

HAMILTON, Bermuda — Wartime spymaster Sir William Stephenson, the man Winston Churchill called “Intrepid,” died at his Bermuda retirement home and was buried today in a secret ceremony, a local undertaker said.

Stephenson, 93, was the subject of the book “A Man Called Intrepid,” a history of his World War II espionage activities. He died on Tuesday.

As British security coordinator in the Western Hemisphere during the war, he launched a program of Anglo-American cooperation and espionage that was decisive in the fight against the Nazis.

Shunned Public Eye

The details of those exploits did not become known until the 1970s. He had retired by then, moving to Bermuda in 1968.

Stephenson stayed out of the public eye until the 1987 scandal over “Spycatcher,” a book written by former intelligence agent Peter Wright, which the British government sought to suppress.

Stephenson said he believed the late Sir Roger Hollis, who had been head of British MI5 intelligence, was a Soviet double agent, a key assertion of the “Spycatcher” book.

“Hollis . . . was a bad egg if ever there was one,” he told the Royal Gazette in Bermuda in July, 1987.

Born in Winnipeg, Canada, the son of a lumber mill owner, Stephenson became an engineer, was gassed in World War I and sent to England to convalesce. He later joined the Royal Flying Corps and downed 26 enemy planes.

During the 1920s he made a fortune through business ventures and his invention of the wirephoto. He was also amateur light heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Sent to New York

In 1940, Churchill sent him to New York. Officially, he was to establish an organization to protect British shipping and counter Nazi spies.

In fact, his assignment had a much wider scope. Churchill called it “Intrepid.”

From an office in New York’s Rockefeller Center, he operated a vast covert intelligence operation.

By the summer of 1940 most of Europe already had fallen to the Nazis. The United States showed no sign of entering the war.

Stephenson had to counter American isolationism and gain support for the Allied war effort. He was to pass on Allied scientific secrets to the United States, train agents to work in Europe and break enemy codes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.