COLUMN ONE : Political Prisoner or Killer? : Canada has always rejected pleas of fugitive Americans claiming asylum from persecution. The case of a former Playboy Club waitress has many Canadians calling for a different outcome.

- Share via

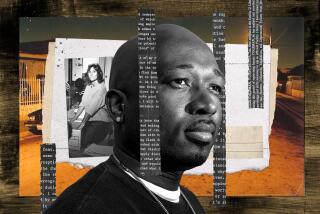

TORONTO — The case of Lawrencia Bembenek, now in its 11th year, has from its outlandish beginnings been ripe for true-crime miniseries treatment. The gist of the story to date:

- Bembenek, a pin-up model and sometime Playboy Club waitress, is convicted of the brutal, execution-style murder of her husband’s first wife in a tract house hard by a Wisconsin interstate while the victim’s two young sons scream in the next bedroom.

- Bembenek’s policeman husband stands loyally by her and weeps as the guilty verdict is read. But he himself negotiates a grant of immunity from prosecution and later calls her a “demon,” capable of everything she is charged with.

- Sentenced to life in prison, Bembenek rails against the Milwaukee police--presciently enough, it may seem, now that, among other derelictions of duty, the force has been shown to have overlooked the famously gruesome serial murders of Jeffrey Dahmer with a singular callousness.

- With photos of the nude antics of off-duty cops to bolster her case, Bembenek, briefly a policewoman herself, accuses the force of hypocrisy and discrimination and some officers of chumminess with Milwaukee’s drug underworld. For telling the truth about the city’s finest, she says, she was framed for first-degree murder.

- Eight years into her sentence, after the denial of two motions for new trials and the failure of three appeals, Bembenek crawls out a prison laundry room window and beats it to Canada with a new boyfriend who helped bust her out. Back home, enchanted Wisconsinites grill “Bambiburgers” and go about with “Run, Bambi, Run” bumper stickers on their cars.

- Months later, the “America’s Most Wanted” TV show features her case, and a Santa Barbara viewer-tipster, just back from a Canadian vacation, notifies police that she waited on his table in the Lake Superior port town of Thunder Bay. Police find her living there under an assumed name, quietly working as a waitress, teaching aerobics and tending a house cat. They haul her away, and her incredulous restaurateur-employer says he’s good for bail money.

Bembenek’s tale has everything, a tidy compendium of trash television themes: beauty, passion, the unwinding of love, murder of a very dark stripe, crookedness, a web of lies and evasions, the grubby folkways of an urban police force in trouble--and almost every possible attendant circumstance of each of these old chestnuts.

And now, it would seem to have reached the far shores of chutzpah as well, for Bembenek, upon her discovery and rearrest in Ontario, has announced that she is not a convicted killer fleeing justice but a political refugee, in flight from persecution in the land of the free.

Implausible though her claim may sound at first, Canadian immigration authorities are seeing to it that Bembenek gets a comprehensive hearing. And as the run-up to that hearing unfolds, no small number of Canadians are siding with her in dead earnest.

“This lady has been wronged, and it’s time that Canadians do what Canadians are known for: Stand up for what’s right,” says Steven Le Lacheur, a trucking-fleet operator who, from his Ontario living room, has organized a Free-Bembenek support network that he says stretches from Quebec to British Columbia.

Canada’s open-mindedness toward Bembenek surprises because, after all, America is a lot like Canada, a modern democracy. Canada regularly takes in refugees from undeniably troubled and violent patches of the globe such as Somalia and Sri Lanka--but America, for all its excesses and disappointments, is supposed to be something else, something much better.

South of the 49th Parallel, the assumption here has traditionally been, the courts are fair--pretty much like Canada’s. The police may have their problems, but they are not, as a rule, Third World bully-boys in sunglasses, cavalry boots and epaulets. There are no death squads. Prosecutors may overdo it, sure, but the system has self-correcting mechanisms. Only in a violently stretched anti-American imagination do the innocent fall prey to railroading and persecution in a place like Wisconsin.

Upshot: For the Canadian government to find Bembenek a refugee and permit her to make a life here would be a terrific slap in the face of Uncle Sam.

So, while Americans have sought asylum here before, the Canadian authorities have never once bought the proposition of an American political prisoner. All American asylum-seekers have had their hearings, alongside the more commonplace Salvadorans and mainland Chinese--and all the Americans have eventually been deported. The Canadian Department of Immigration is likewise trying to deport Bembenek right now.

But Bembenek’s case may be headed for a different outcome.

Already, a team of big-time lawyers, the toast of Toronto’s buttoned-down Bay Street, has taken on her refugee claim, with their meters shut off.

“If we walked away from it, then we would be acquiescing in what happened,” says lead lawyer Frank Marrocco, hinting at the alleged frame-up from his spectacularly panoramic perch 60 floors above Lake Ontario in downtown Toronto.

A New Forum

Marrocco, a former prosecutor and the author of a definitive treatise on Canada’s immigration code, says that if members of the Milwaukee law-enforcement community did indeed set up Bembenek to take the fall for a murder, “then that amounts to persecution.”

“What else would you call it?” he asks.

Back in Wisconsin, Bembenek’s prosecutors aren’t happy to see Marrocco and his fellow Canadians assuring her a new forum to plead her case.

“This should be fought out in a courtroom, that’s our opinion,” says Robert Donohoo, deputy district attorney for Milwaukee County. If Bembenek has anything new to say, Donohoo adds, she should submit to the American criminal-justice system and not try to persuade Canadians who “are forming opinions without reading (the record of) the original trial.”

Even as Bembenek works to convince Canada she is a refugee, Wisconsin has pressed for her extradition in separate legal proceedings.

“This just shows the lengths that they’ll go to,” said Bembenek in a recent interview at the suburban Toronto jail where she is being held. “They couldn’t even let my refugee claim run its course.”

No wonder the Wisconsin prosecutors are unhappy. By now, Bembenek’s Canadian lawyers have helped assemble new evidence which--if it can be confirmed--would make a hash of her original conviction.

The most compelling of their findings purports to show that the revolver introduced into evidence at her trial 10 years ago could not have been the murder weapon.

“If the gun isn’t the gun, then Lawrencia Bembenek can’t possibly be the murderer,” says John Callaghan, another of her lawyers. “If the gun isn’t the gun, then what did she murder (the victim) with--a saucepan?”

An Uphill Battle’

To keep Bembenek in Canada, the lawyers will ultimately have to persuade a two-member refugee panel that if she returns to America, she will face persecution, as it is defined by the United Nations. Marrocco concedes this will be “an uphill battle.” One panelist comes from the Immigration Department itself, the very government body that wants to put Bembenek on the first plane south.

(An immigration spokesman says this panelist represents an independent branch of the department and is not subject to political pressure. In any case, if the other panelist accepts Bembenek’s refugee claim, she is home free no matter what the man from immigration may say.)

As the Canadian lawyers have set about presenting their case, the Canadian media have warmed to Bembenek. Television is proving to have a weirdly decisive role in the 33-year-old’s fortunes: Just as it was an episode of “America’s Most Wanted” that ended her fugitive’s life, it is the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. that has now begun to fuel pro-Bembenek sentiment.

Last fall, the CBC, a respectable network known for its sober news programming standards, aired a widely viewed documentary that left the unmistakable impression that Bembenek had been framed. A CBC spokeswoman reports an unusual jump in viewership on the night the documentary ran, and Bembenek says she “got a lot of mail from all over Canada after it aired.”

As it happens, Bembenek may have fetched up in Canada at a moment when ordinary Canadians are well-primed to accept the “I’m innocent” arguments of underdog convicts. Canada recently saw a Micmac Indian released from a Nova Scotia prison, 11 years after his wrongful conviction for murder. A follow-up inquiry concluded that he was indicted and tried in the first place principally because he was an Indian.

And it was a team of dogged Canadians who helped assemble the appeal that ultimately exonerated Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, the black American onetime middleweight boxing contender who was convicted of triple homicide by an all-white jury in New Jersey and spent 20 years behind bars. Carter now lives in Toronto and is active on the Canadian lecture circuit.

Bembenek supporter Le Lacheur--who has offered to put up his house and trucking business as surety if Bembenek is freed on bond--cites these and other cases in telling why he now wants to help her. He says he videotaped the CBC documentary and has replayed it for about 100 Canadians, all but two of whom promptly joined his “crusade.”

New Wisconsin Probe

As interest in and curiosity about Bembenek mount in Canada, officials back in Wisconsin have begun an extraordinary closed-door investigation into her case, probing allegations of perjury, the mishandling of evidence introduced at her trial and other nettlesome issues inconveniently high in number.

The Milwaukee inquiry, to which a special prosecutor was named, began in November and is expected to continue for months.

In the end, the Canadian refugee panel may decline to second-guess the American criminal-justice system and decide to wait for the Wisconsin findings before ruling on Bembenek’s bid for asylum.

Meanwhile, Bembenek waits in jail, under conditions that she says are “probably the hardest of the last 10 years,” because the jail is in essence a holding pen and not set up for long-term prisoners.

“I can’t complain,” she adds quickly, speaking by telephone through a plexiglass barrier in the jail. “The last thing I want to do is spark a response where the (Canadian) public would say: ‘Oh, you don’t like it here? Then go back where you came from.’

“Some Canadians say, ‘If she has all these points in her favor, let her go back to the United States and get a new trial,’ ” she says. “A lot of them say, ‘Fine, we don’t think she’s guilty either, but it’s not Canada’s problem.’ I just don’t have any hope, should I be forced to go back (to America). I have no reason to believe I could ever get justice back there.”

The saga of Lawrencia Bembenek--known in the popular cross-border media as “Bambi,” a cutesy nickname she doesn’t like--has been stretched across a rack of prurience and lowbrow sociology.

It began at about 2:15 one May morning 11 years ago, when two small Milwaukee boys awoke to find someone--they testified it was a man--in their bedroom, clamping a hand over the elder child’s mouth. Screams and scuffling followed, the intruder dashed out of the room, and the terrified boys heard what they thought was a firecracker exploding in their mother’s room. They ran to find the woman loosely bound and gagged, bleeding on her bed.

Thirty-year-old Christine Schultz had been shot point-blank in the back. She bled to death in minutes, without naming her killer.

Quest for Killer

Schultz’s former husband, policeman Elfred Schultz, became a suspect for a time; the couple’s divorce had been unusually bitter. But since Elfred Schultz could prove he was on duty on the night of the murder, the search for a killer ultimately led to his second wife, Bembenek. The authorities argued that she had expensive tastes in clothes, jewelry and travel; they said she killed Schultz to unharness her husband from a crushing yoke of alimony and mortgage payments.

From the first, Bembenek’s case created a sensation. Lawyers, detectives, newspaper reporters--seemingly everyone involved in the investigation--ran on and on about her looks and presence. She was a tall, slender bottle blonde; she had worked as a pin-up model and a waitress at the now-defunct Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, Wis.

She “liked to live in what I would refer to as the fast lane,” the prosecutor told the Milwaukee County jury that convicted her.

Maybe yes, maybe no, but Bembenek had another side: For one thing, she gave money and time to mainstream feminist causes such as Women Against Rape and the Milwaukee Women’s Political Caucus. And as a Milwaukee police cadet, she had spoken out about the “insensitive” way a police academy instructor spoke of gang rape to fellow recruits and endured the ridicule of male classmates as a result.

While still a rookie, Bembenek was discharged for filing a false report about a fellow recruit’s alleged drug use. The firing enraged Bembenek, who came to suspect that the police department was taking federal affirmative-action money to hire women and members of racial minorities, then unloading the newcomers for trivial offenses once the cash was in the till.

Bembenek began helping federal officials investigate the possible misuse of funds. She assembled a remarkable portfolio of evidence: It featured photographs of white, male Milwaukee police officers and their friends, striking nude poses in front of a beer-drinking crowd in a county park while children looked on studiously from the sidelines.

(Canadians who watched the CBC documentary got to see full-color reproductions of the frontal nude photos--one of which was of none other than Elfred Schultz. Bembenek hadn’t yet met him in his Dionysian days. The beer-soaked frolic, which started out as an annual wet-T-shirt contest and went downhill from there, was organized by a Milwaukee tavern said to be a favorite hangout of various low-lifes, drug dealers and, oddly enough, off-duty cops.)

Bembenek’s point in collecting the pictures was that the cops publicly cavorting in the altogether were, at the very least, breaking departmental rules and contributing to the delinquency of minors--but no one was firing them, because they were white and male.

She made herself few friends when she handed in the photos to the police department’s internal-investigations unit. Her supporters believe that her departmental enemies pinned Christine Schultz’s murder on her to get her out of the way, thereby queering a comprehensive probe of police corruption.

And indeed, the assistant U.S. attorney who was looking into the misuse of affirmative-action funds in the early 1980s has testified that when Bembenek was indicted, his investigation of the Milwaukee police was put out of business.

All the same, a jury convicted Bembenek in 1982, on the basis of several pieces of circumstantial evidence--the evidence that is now under attack in the Canadian refugee proceedings.

Bembenek’s Canadian lawyers argue not only that the evidence against her is flimsy; they suggest that it may have been tampered with as well. The legal record is extraordinarily complicated, and studded with anomalies, but a few examples set the tone.

- The murder weapon:

At Bembenek’s trial, ballistics experts testified that it was Elfred Schultz’s off-duty revolver that had fired the bullet that killed Christine Schultz. And Elfred Schultz himself testified, under a grant of immunity from prosecution, that the gun was his, and that he had left it at home in a gym bag on the night of the murder.

Bembenek, home alone that night, was the only person with access to it. Their apartment was 16 blocks from the victim’s house. At the trial, the prosecutor brought up her excellent physical condition and suggested that she had jogged to and from her murder chore while her husband worked the night shift.

In 10 years, no one challenged the prosecution’s ballistics work or Elfred Schultz’s testimony. But now Bembenek’s Canadian lawyers are saying there is more than ample reason to do so.

As it happens, Christine Schultz’s murderer pressed the gun deep into her upper back while pulling the trigger. The muzzle left a perfect, doughnut-shaped impression in her skin. The impression was 17.21 millimeters across. Schultz’s off-duty gun, it turns out, has a muzzle diameter of just 13.29 millimeters.

Pathologists’ View

Frank Marrocco and his associates have taken depositions from four prominent forensic pathologists who say a gun muzzle of one size cannot leave an impression of another size--and that as a consequence the gun presented at Bembenek’s trial could not have been the murder weapon.

If this argument succeeds, it will collapse the foundations of Bembenek’s conviction. Jurors said, at the time of her trial, that it was the gun evidence, more than anything else, that had made the case against her.

But Donohoo, the deputy district attorney back in Milwaukee, belittles the gun-muzzle discrepancy, saying there are virtually no laboratory data on muzzle imprints. Besides, his office has produced yet another forensic pathologist, who says gun muzzles don’t necessarily have to match the impressions left in the bodies of gunshot victims, because gun blasts can stretch the human epidermis.

That leaves Bembenek’s prosecutors and defenders arguing back and forth over whose experts are the more reliable.

Donohoo says he thinks the muzzle matter ought to be brought before an American court, rather than left to the Canadians to sort out. He says his office has proposed a post-conviction hearing on the issue of muzzle imprints.

But for Bembenek, who has lost every legal encounter south of the border, returning to a U.S. courtroom now would be stepping into the tiger’s mouth. She and Marrocco aren’t taking Donohoo up on his proposal.

- Hairs taken from the gag:

At Bembenek’s trial, the prosecution produced strands of bleached-blond hair and said they had been taken, during the autopsy, from the gag that had been tied over the murder victim’s mouth. The hair was analyzed and said to be compatible with Bembenek’s.

After the trial, though, the possibility arose that strands of Bembenek’s hair might have been planted on the gag.

The first suspicion came in 1983, when medical examiner Elaine Samuels, who supervised Christine Schultz’s autopsy, said she had found no blond hairs whatsoever during her examination--only brown hairs belonging to the victim. She said she had sealed the brown hairs in an envelope and sent it to the state crime lab for analysis.

Laboratory Records

At the lab, records show, the envelope was checked out by a police officer, then returned. When it was returned, it was found to contain blond hairs.

Bembenek’s supporters argue that the blond hairs were put into the envelope as part of the frame-up. Their charge has won over some senior figures on the margin of the Bembenek case, including Milwaukee County’s former chief medical examiner, Chesley Erwin, who has called for a review of Bembenek’s conviction.

“Key physical evidence . . . was tampered with prior to her trial to secure her conviction,” Erwin alleges in a recent affidavit.

Donohoo says, however, that Samuels is “a little eccentric” and “not that credible” on the matter of the hairs. He says the blond hairs were on the gag right from the beginning, no matter what Samuels and her boss Erwin may say. Police checked the envelope out of the crime lab not to plant hairs in it, he said, but to use the materials in interviewing a witness.

- A wig in a drainpipe:

Christine Schultz’s two young sons caught more than a glimpse of their mother’s killer. Both boys said the intruder was a large man dressed in green, with red hair pulled back in a ponytail.

Bembenek at the time had collar-length bleached blond hair.

This additional discrepancy would seem to help her--except, as the prosecution pointed out, she had worked as a department-store window-dresser and at the Playboy Club. In both places, she would have had access to wigs.

And, eureka, not long after the murder, Bembenek’s landlady phoned the police to report that a toilet in her building had overflowed and a wig had been pulled out of the drain. It was a Y-shaped drainpipe, leading away from two toilets: One in Bembenek’s and her husband’s apartment, and another--the one that had overflowed--in the apartment next door.

Prosecutor’s Allegation

Had Bembenek committed the murder in disguise, then jogged home and flushed the wig away? That’s what the prosecution alleged.

But there was an odd--and perhaps exculpatory--detail that didn’t emerge at the trial. Bembenek’s next-door neighbor, Sharon Niswonger--the one whose toilet ran over--now says in a sworn statement that the day before her plumbing problems started, a former friend of Bembenek had stopped by out of the blue, proposed that they go to the gym together, and asked to use the bathroom.

The visitor, a woman, was by then on bad terms with Bembenek. She was the last person to use the toilet before it stopped up.

Niswonger said the visit “troubled” her, the implication being that the visitor had plugged the drain with a wig on purpose, perhaps as part of a broader plot to implicate her ex-friend. Niswonger added that none of this ever came out at the trial; she answered only the questions she was asked on the stand, and no one ever asked about mysterious visits from Bembenek’s detractors.

Donohoo says his office has “powerful evidence to show that what (Niswonger) said just isn’t true,” but can’t say more because of the proceedings in Milwaukee.

Problems with the muzzle imprint, the blond hairs and the wig in the toilet aside, Bembenek’s case teems with deficiencies in simple police craft. Investigators didn’t bother confiscating the alleged murder weapon for three weeks, plenty of time for it to be switched with another gun. The detective who first examined it threw away his notebook and testified that, in any case, he never wrote down the serial number.

A green-clad potential suspect was seen by several witnesses in the murder victim’s neighborhood at about the time of the killing. The victim’s friends have revealed that her ex-husband used to beat her; her lawyer has stated that she feared for her life and thought she was being followed.

And Elfred Schultz has turned out not to be the world’s most reliable witness; it now emerges that at the time of Bembenek’s investigation and trial, he was undergoing a police investigation of his own, for giving false information in unrelated matters. He resigned when the police confronted him with their findings, but the jury never got to hear about it.

There was plenty more the jury didn’t get to hear, Bembenek’s supporters say. In fact, one of Bembenek’s appeals was based on the question of her defense lawyer’s competence. Although she lost the appeal, that lawyer has since been disbarred for misconduct in another case. He now says he believes that she is guilty (choosing an appearance on the “Geraldo” TV show to say as much). So does her ex-husband.

Coming to Canada and finding lawyers who could present this complicated information coherently has been “a godsend,” says Bembenek, who seemed surprisingly relaxed and animated in the interview, despite her bleak surroundings.

She said her spirits are incomparably higher than they were at the time of her Wisconsin jailbreak when, she says, she believed she had exhausted all avenues of appeal and “felt dead on my feet” with hopelessness.

To her supporters’ arguments, Donohoo responds that Bembenek’s case has been thoroughly investigated--much more thoroughly than they realize. The facts, he says, lead inexorably to her guilt.

“The media have taken one side, and that’s the glamorous side,” he said. “The allegations (of a frame-up) are easy to portray. They fit nicely, and they have a certain appeal. But appeal in the courtroom doesn’t count. That’s where the facts count. Every time she has come to the courtroom, she has lost on the merits.”

So far.

Bembenek Case Ripe for TV Drama

Here are highlights to date of the case of Lawrencia Bembenek, now in its 11th year:

* Bembenek, a pin-up model and sometime Playboy Club waitress, is convicted of the brutal, execution-style murder of her husband’s first wife in a tract house next to a Wisconsin interstate, while the victim’s two young sons scream in the next bedroom.

* Bembenek’s policeman husband stands loyally by her and weeps as the guilty verdict is read. But he negotiates a grant of immunity from prosecution and later calls her a “demon,” capable of everything she is charged with.

* Sentenced to life in prison, Bembenek rails against the Milwaukee police--a force shown to have overlooked the famously gruesome serial murders of Jeffrey Dahmer with a singular callousness.

* Using photos of the nude antics of off-duty cops to bolster her case, Bembenek, briefly a policewoman herself, accuses the force of hypocrisy and discrimination. She also says some officers are chummy with Milwaukee’s drug underworld. For telling the truth about the police, she says, she was framed for first-degree murder.

* Eight years into her sentence, after the denial of two motions for new trials and the failure of three appeals, Bembenek crawls out a prison laundry-room window. She flees to Canada with a new boyfriend who helped her escape. Back home, enchanted Wisconsinites grill “Bambiburgers” and go about with “Run, Bambi, Run” bumper stickers on their cars.

* Months later, the “America’s Most Wanted” TV show features her case. A Santa Barbara viewer, just back from a Canadian vacation, notifies police that Bembenek waited on his table in the Lake Superior port town of Thunder Bay. Police find her living there under an assumed name, quietly working as a waitress, teaching aerobics and tending a cat. They haul her away. Her incredulous restaurateur-employer says he’s good for bail money.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.