The Latest in Computer Viruses: Smallpox : Health: Researchers are putting the genetic code for the virus on floppy disks. The hope is to make disease extinct by December, 1993.

- Share via

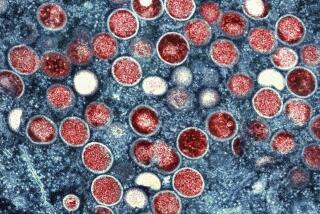

The smallpox virus, perhaps the most destructive infectious agent in human history, someday soon will be no more than a mass of magnetic signals stored on a floppy disk.

Within the next three months, a team of American biologists will finish sequencing the genetic code of the virus, which has been extinct in the wild since 1977 and whose captive stocks are now handled with the care normally reserved for substances such as plutonium.

Determining the microbe’s DNA sequence is the essential step that will culminate in destruction of all samples of the virus no later than December, 1993. Those samples are held in only two places: the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta and the Research Institute for Viral Preparations in Moscow.

If the plan succeeds, the smallpox virus will become the first life form intentionally wiped off the Earth.

Although that event would be without precedent, it would not be the first precedent set by the variola virus, the scientific name of the microbe.

In January, 1967, the World Health Organization launched an international effort to eradicate smallpox within 10 years. The goal was technically possible for four reasons. First, the virus infected only people, so once the chain of human transmission was broken, the disease would die out. Second, smallpox is an easily diagnosed disease, so outbreaks could be found. Third, survivors had lifelong immunity. Most important, a cheap and effective vaccine existed.

Nevertheless, no disease had ever been stamped out, and even if smallpox was a good candidate, the timetable seemed overly optimistic. Smallpox was active in 44 countries. (Much of the developed world had been free of it for decades, with the last recorded American case in 1949.) Of the estimated 10 million to 15 million new cases a year, about 2 million were fatal.

The goal of universal immunization proved infeasible, especially in places such as Africa and India, where it was most needed. More successful was aggressive “case finding” and targeted vaccination, a strategy that required even more work. In April, 1975, for example, about 115,000 health workers went house-to-house in India looking for cases of smallpox.

Against the odds, and in what is undoubtedly public health’s greatest triumph, the campaign succeeded. On Oct. 26, 1977, a cook in Somalia became the last person known to contract smallpox naturally. The World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated in May, 1980.

In the years since, samples of the virus collected around the world were consolidated at the current repositories. Although it is unlikely that any country could reclaim its samples, national “ownership” is still duly noted. CDC’s freezers hold U.S. Army, Dutch, Japanese and English smallpox virus. The Russian institute stores those of the former Soviet Union, Brazil, India, Ethiopia, and several other African and Asian countries.

The idea of destroying the stocks came from developing countries uncomfortable with the notion that only superpowers held them. Two years ago, Louis W. Sullivan, secretary of health and human services, announced that the United States would destroy the CDC stocks after sequencing the virus’s genes. He invited the Soviets to do the same, and they agreed.

There are two distinct forms of smallpox. Variola major was the deadlier form, with a mortality rate of up to 20%. Variola minor had death rates of less than 1%. The American team is sequencing the DNA of a particularly virulent strain of variola major virus isolated in Bangladesh in 1975.

Biologists at the CDC have cut the virus’s DNA into pieces and inserted them into loops of bacterial DNA called plasmids. This makes the material easier to study and reduces human contact with the whole virus. The actual sequencing is done in a laboratory at the National Institutes of Health. The information is stored on a computer disk and will ultimately be published.

Russian scientists are sequencing a variola minor virus. The two teams hope to sequence as many as five strains if time permits.

Scientists hope that even after the virus is gone, questions that remain may be answered as science gains greater ability to “read” DNA.

But even if some knowledge is irretrievably lost, the scientific community seems in favor of the virus’s destruction. Several years ago, a survey of 62 virologists from 22 countries found only five opponents.

To date, no one has come forward to argue that the variola virus has a “right” to exist or that it should be preserved as a matter of principle.