Caltech Captures Key to a Mystery of the Heavens

- Share via

Caltech scientists have captured images of the most powerful bursts of energy in the universe, solving perhaps the biggest mystery in modern astronomy.

Because the puzzling burst of gamma rays was located at least 2 billion--and perhaps even 7 billion--light-years away from Earth, it would have to be stupendously bright--”the most brilliant flashes in the universe,” said Caltech astronomer Shri Kulkarni. “It boggles my imagination to think what it means to be a billion, billion times brighter than the sun.”

Such enormous outpourings of energy must be created by something truly extraordinary. “We know they’re not Klingons,” Kulkarni joked.

UC Santa Cruz astrophysicist Stan Woosley said: “This is a major breakthrough that we’ve all been waiting for for 30 years.”

The discovery should finally allow researchers to learn something concrete about these elusive events, which have prompted astronomers to come up with hundreds of possible explanations.

“It’s very exciting and confusing,” said Caltech astrophysicist Roger Blanford. “This is a mystery that’s been around since the 1960s. There’s no shortage of imagination [about what it might be].”

U.S. spy satellites serendipitously picked up cosmic hot flashes while snooping for secret Soviet nuclear explosions in the late 1960s. Since then, astronomers have been struggling to figure out what could be sending out such intense blasts on a daily basis.

More powerful even than X-rays, gamma rays are the most energetic form of light. Only the most violent events in the cosmos--such as colliding collapsed stars or black holes--could produce such outpourings.

The bursts flash randomly in the sky at the rate of about one a day. Because they usually fade in seconds, astronomers haven’t been able to trace one back to its lair. However, in February, a new Italian-Dutch satellite was able to narrow the location of a burst sharply enough to alert ground-based telescopes, which went back for a second look and found a diffuse visible glow.

When another large burst of gamma rays went off last Thursday, astronomers around the world were ready and waiting. First, the satellite tracked down the telltale X-ray afterglow that normally accompanies such bursts. Then the optical astronomers looked for a visible signal, and Caltech astronomers at Palomar Observatory saw what looked like a flickering star-like object.

By Saturday, the Caltech team had focused the huge 10-meter Keck Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, on the rapidly fading object. Only the Keck--the largest telescope in the world--can spread out the light from such a faint object and analyze its spectrum. Dark lines in the spectrum of the light revealed the clear fingerprints of a large intergalactic cloud sitting in the line of sight between the energy source and Earth.

By reading the spectral lines, astronomers can determine the location of the cloud, which is at least 2 billion light-years distant. The gamma rays apparently came from behind the cloud, which would mean the source is even farther from Earth. Scientists say it could be as distant as 7 billion light-years, or halfway back to the origins of the universe.

Since the February burst, the Caltech team had been waiting to catch one of the bursts with the sharp eyes of the Keck. “This time we had a team together, we were prepared,” said Caltech astronomer Mark Metzger. “We’re really able to measure this thing well. It will be a real breakthrough to understanding the mechanism [that produces the bursts].”

Woosley said theorists have come up with more than 140 different models to explain the origin of the bursts. What that means, he says, is: “No one knows.”

For a long time, astronomers were divided into two schools of thought: those who believed the bursts were local events, occurring within the Milky Way galaxy, and those who thought they were coming from the far reaches of the cosmos. Bursts from the edges of the universe would have to be far brighter--among the most energetic events in the cosmos--to flash with the same intensity.

“Now we’ve solved the mystery of where they’re coming from,” said Metzger. “That puzzle has been cracked.”

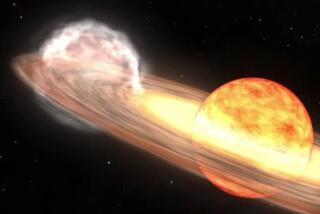

The only force strong enough to produce such enormous energies is the gravitational pull of a black hole or collapsed star. Collapsed stars--or neutron stars--are so dense that even a small passing piece of asteroid falling on one would cause nuclear explosions. If two such stars collided, they could easily produce powerful, focused jets of gamma rays.

The bursts would appear to last very briefly from the point of view of Earth’s orbit, Blanford said. However, the effect is part illusion, because time can stretch out or condense depending on one’s point of view, according to Einstein’s special relativity. The jets would appear to last longer on the star.

At the same time, the fireball produced by the collision would continue to glow in X-rays for several days, and in weaker, visible light for weeks or months. Researchers speculate that they are looking at the remnants of that visible glow as it gets filtered through the intervening cloud.

Still, all these scenarios are for now mostly speculation. “There are many, many models--all of them [fantasies] like the tooth fairy,” said astrophysicist Chryssa Kouveliotou of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. “Astronomy is like archeology. We’re looking into the past. We’re detectives, trying to get as much information as we can to tell us about our universe, and about how we came to be.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Light Show

The leftover glow of a gamma ray burst seen in these images is at least 2 billion light years away, suggesting that it is the most powerful outpouring of energy in the universe--”a billion, billion times brighter than the sun,” one astronomer said. Such bursts, one of astronomy’s greatest mysteries, were first noticed 30 years ago. But scientists could not pinpoint their source until now.

Source: Palomar Observatory