Passive Aggressor

- Share via

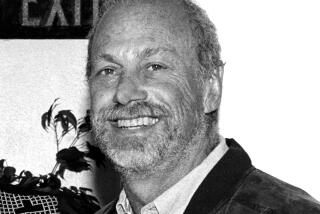

MIAMI — In his 36 years as a lawyer, Stanley M. Rosenblatt has earned a reputation in south Florida legal circles as a passionate and pugnacious litigator. Now, at age 60, he is involved in the trial of his life.

Jury selection began Monday and is expected to last at least another week in a suit that Rosenblatt has filed against the tobacco industry on behalf of 60,000 U.S. flight attendants. It is the first passive-smoking case--and the first class-action suit against the tobacco industry--ever to go to trial.

And the way Rosenblatt has gone after Big Tobacco speaks volumes about his maverick and combative style, both his allies and adversaries say.

While many of the nation’s wealthiest plaintiff’s lawyers have banded together for an all-out attack on the $50-billion industry, Rosenblatt’s tiny firm--consisting of himself, his attorney-wife Susan and three other lawyers--has shunned alliances. The Rosenblatts are going it alone in the flight attendants case and an even bigger tobacco class action, known as Engle vs. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, to be tried here in September.

“He’s a loner, no question about that,” said Miles A. McGrane III, a Miami defense attorney who has repeatedly battled Rosenblatt.

“I’ll bet you’ve never seen a law firm so small take on such a target without looking for allies out there to help them,” McGrane said. “I think he enjoys the image right now of riding out and jousting a windmill.”

But Rosenblatt does not consider his case quixotic.

“I think I have a good shot at winning, but I do not underestimate them,” Rosenblatt said, referring to the crowd of talented defenders on the tobacco firms’ side.

“They’re good lawyers,” he said. “Not lawyers I like very much, but they’re good lawyers.”

Early in the case, Rosenblatt displayed his take-no-prisoners style, causing a witness he thought was stonewalling him to break down in tears. After Michael Rosenbaum, executive vice president of Liggett owner Brooke Group Ltd., testified in his pretrial deposition that he had no clue whether smoking causes cancer, Rosenblatt asked: “In all candor, wouldn’t you equate those who say cigarettes don’t cause cancer to those who assert the Holocaust never happened?”

Rosenbaum bristled and called the question “demeaning.” But when Rosenblatt persisted, Rosenbaum broke down and cried.

“I felt bad for him,” Rosenblatt said, “because I felt he cried because he agreed with me.”

Although Rosenblatt has won his share of large verdicts, his biggest cases until now have had a distinctly local dimension.

Many were medical malpractice cases or suits filed for people who had suffered traumatic injuries. Three years ago, for example, Rosenblatt persuaded a jury to award $6 million to a teenager who became paralyzed after diving into shallow water from a motel pier posted with “no diving” signs.

But Rosenblatt had never been an anti-tobacco crusader, nor had he picked a fight with so powerful a foe.

Then in 1991, he was visited by Norma Broin, a Mormon and life-long nonsmoker who had contracted lung cancer after 13 years of serving drinks and snacks in smoky airline cabins. Broin had already been turned down by other lawyers, including veteran anti-smoking activist Matt Myers, who, Broin said, told her he could not bear the expense of taking on the tobacco companies.

(Myers, now executive director of the National Center for Tobacco-Free Kids, said he declined the case for a “host of reasons unrelated to the merits.”)

Rosenblatt also meant to say no.

“There was no way we were going to get involved in the case, because taking on the tobacco industry is like taking on a country,” he said. “They’ve got all the money in the world.”

But after satisfying himself that Broin’s illness was due to secondhand smoke, Rosenblatt changed his mind.

“Once I started studying the tobacco industry and all the harm they do, it became a cause very quickly,” he said.

The Rosenblatts have taken the Broin and Engle cases on contingency and have invested close to $1 million in trial preparation--though they say they don’t know the exact amount.

“We’re into denial on that,” Susan Rosenblatt said.

While these costs would sink many small firms, they pale before the investment of the Castano group, a consortium of more than 60 plaintiffs firms that joined together in 1994 to battle the industry. The Castano lawyers have filed about 15 statewide class-action suits and are somewhat miffed that the Rosenblatts would not deign to join their ranks. “They’re very independent, they want to go their own way, and they have,” said attorney Russ Herman, a Castano group leader.

Consumer lawyers face long odds when fighting big business, Herman added, but “if you’re into strategy, skill and information sharing, then you even the playing field and you can go toe-to-toe with Goliath because you’ve got a terrific support group out there.”

Shifting to Shakespeare, he quipped: “All I know is, when Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane, I’d rather have a whole forest out there than a single tree.”

For his part, Rosenblatt said he was uncomfortable with the Castano strategy of seeking damages for addiction, but not for injuries sustained through years of smoking. In other words, if the suits are successful, the industry would pay damages for what smokers spent on cigarettes and cessation programs--not for the illnesses they allegedly contracted from their habits.

“It looked like a gimmick for lawyers whose bottom line was making money,” Rosenblatt said.

It is not the first time Rosenblatt has bearded presumed allies.

After the lethal chemical disaster in Bhopal, India, in 1984, Rosenblatt called on the victims’ U.S. lawyers (many of them now in tobacco litigation) to work the case pro bono.

In an op-ed piece in the National Law Journal, Rosenblatt later said his suggestion “was rebuffed almost unanimously by as greedy and shortsighted a group of professionals as I have ever seen.”

Both Rosenblatts moved from New York to south Florida as children. Stanley was a basketball star in high school; Susan, now 46, was a prodigy, starting college at 13 and earning a law degree at 21.

With nine children, ages 4 to 16, to go with their busy law practice, the Rosenblatts’ lives can be helter-skelter. Exhibit A is their 8,000-square-foot Miami Beach home, which once belonged to orange juice promoter and anti-gay activist Anita Bryant.

“She came to see it once and was very disillusioned . . . about all the chaos,” Susan Rosenblatt recalled. “There were a lot of little kids running around, and our kids are very messy.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.