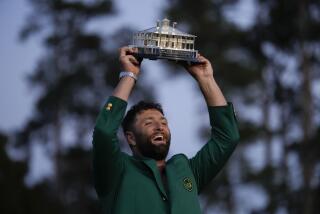

The Suits Behind the Green Jacket

- Share via

What makes the Masters a “major”?

Better yet, should it be?

The short answer to the first question would be, “Bobby Jones, Herb Wind and spring training.”

The answer to the second question is a bit more complicated. Controversial.

The Masters was the brainchild of the most celebrated golfer of the first half of this century, Robert Tyre Jones.

Bobby was the first--and still only--man to win the British Amateur, the U.S. Amateur, the British Open and the U.S. Open the same year. It was the so-called “Grand Slam,” a phrase coined in honor of the close relationship between the game of golf and the game of bridge in those times.

Jones’ prestige was such that, when he constructed his course out of some of the most magnificent flora in the Southeast, the press had to pay attention. So, because his tournament was scheduled at the end of baseball’s spring training, the writers, on their way north, dutifully stopped off at Augusta and deferentially covered Bobby’s grand experiment.

It was an “invitation only” tournament--no riff-raff need apply--and, because Bobby remained an amateur, his field was barnacled with them. The entire Walker Cup team was invited, for example. This was usually a collection of Long Island stockbrokers with a nice putting touch who would get together with a band of similarly undistinguished part-time players from England every two years.

Bobby’s tournament was a nice little exercise in manners and a good time was had by all. It even shared in the sports headlines sooner than it might otherwise have when a rare double eagle was scored the second year. Gene Sarazen used it to beat out all those two-handicap Walker Cup players and selected pros.

It was otherwise as private as a cotillion.

Enter Herb Wind. Now, Herbert Warren Wind was a lyrical golf writer who loved the game--and Bobby Jones--and wrote these rhapsodical pieces about the Masters for the New Yorker.

For the good of the game, that was a little like writing them on a monastery wall. But when Sports Illustrated magazine started up in 1954, Herb got a wider and more sports-literate audience, and, in his first year, he got a playoff between Ben Hogan and Sam Snead, no less.

The Masters became Page 1 stuff. The public was fascinated. A tournament that once gave away tickets to swell the gallery became a multimillion-dollar TV show with clubhouse badges being scalped for $12,000 and up. The most difficult ticket in sports.

It grew like crazy. Almost by osmosis, it elbowed aside old-line “majors” like the Western Open, the North and South, and the Metropolitan Open.

It shouldered its way in with the British and U.S. Opens and the PGA.

It probably belongs there now. But did it always?

Probably not. In course beauty--all that forsythia and flowering wisteria and magnolia blossoms--it made St. Andrews look like a rubber-mat track in Peoria. It was a cathedral of whispering pine.

But it was as politically incorrect as the Hapsburg Empire. It invited only 90-some select players. About 150 players tee it up weekly in the ordinary PGA tournament, then they cut it to the low 60 scorers. The Masters didn’t have a cut till 1957.

It was crony golf. Cliff Roberts, the Wall Street arbitrageur who ran the tournament--and the club--for Bobby Jones, was as monarchical as Louis XIV. Or Ivan the Terrible. He wasn’t much interested in democracy.

The Masters didn’t specifically bar African Americans. It simply made the conditions for invitation wholly unrealistic.

It ritually would invite, say, the best golfer in Formosa, or the runner-up in the Portuguese Open, the best golfer in the south of France or the Dutch Open champion. But when I would write a column inquiring why a two-time winner on the American tour, Charlie Sifford, wouldn’t get invited, I would get a letter from Bobby Jones explaining that all he had to do was win the U.S. or British Open or finish better than 16th in the U.S. Open.

Easier said than done for a guy whose race made it difficult for him to tee it up at all in those tournaments. So, I would write to ask why Chen Ching-po, who had done neither of those things, got invited. So had Gary Player, who had done neither the first year he was invited.

Jones was gone when the Masters finally changed the rules to automatically admit tour winners. That was too late for Sifford but in plenty of time for Tiger Woods and, therefore, the rest of the game of golf.

In spite of its undeniable beauty, the Masters, in a real sense, fails to qualify as a major in degree of difficulty of play. There’s no rough at the Masters. You can loosen the girdle and let fly. It thus rewards big hitters inordinately.

The U.S. Golf Assn. has been known to grow hip-high rough for its U.S. Open to frustrate the players and force them to think of accuracy rather than length. The British Open puts its tournaments on seaside courses where strong winds and bad weather make those high, long shots inadvisable.

The Masters has been won an inordinate number of times by the same kind of player--sometimes the same player, period. It used to be won by Hogan-Snead, Snead-Hogan. Then it was Palmer-Nicklaus, Nicklaus-Palmer. Jack Nicklaus won six Masters, Arnold Palmer four. Hogan and Snead won five between them and had a playoff for the fifth.

The headline “Unknown Wins Open” would appear periodically after a U.S. Open. Sam Parks, Tony Manero, an Ed Furgol, Orville Moody, Jack Fleck would emerge. No unknown ever has won a Masters. It has been as formful as a coronation.

You can spray the ball at the Masters. Straight is not a consideration. But you have to be able to get your ball over the crown of the hill on the par-fives. Lee Trevino, for one, never could do that. But Tiger Woods had a wedge second shot to the par-five 15th twice last year.

No one has an advantage putting. The greens are like glass. Your only hope is to get the ball close with your approach. Obviously, this is easier to do with a wedge than a four-wood.

It has become a happy hunting ground for the foreign player of late. The winners of seven of the last 10 Masters have been from abroad--Nick Faldo three times, Sandy Lyle, Ian Woosnam, Bernhard Langer and Jose Maria Olazabal.

Well, why not? More get invited than for any other tournament. Jones-Roberts saw to that.

So, is the Masters a faux major? No, but it found itself a major considerably to its surprise. The grand Bobby probably thought he was creating an event where a fellow amateur might be able to win once in a while. Instead, he has established a hallowed corner of golf that makes those other “majors” look minor. Ask any player if he’d rather win a PGA or a Masters, he’ll look at you as if you’d lost your mind.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.