A tussle over Trestles

This not-so-subtle sign on a wire-topped fence reminds visitors that some of the access along San Onofre State Beach south of the Trestles surf break is restricted by the U.S. Marine Corps. There is a disagreement on whether the famed wave-riding spot should be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Surfers say yes, the Marines say no. A state commission has sided with the surfers. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

A disagreement over a well-known slice of the Southern California coast is threatening to drive a wedge between Marines and surfers, groups that had recently set aside differences and become political allies.

Pelicans and gulls gather along the sand at middle Trestles, oblivious to the wetsuited surfer riding a clean wave at the famed break. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

U.S. Marine Corps infantrymen from Camp Pendleton disembark from an amphibious assault vehicle after coming ashore. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Colorado resident Sue Hayes, with grandchildren Jackson and Alexandra Morse, watch a train pass their spot on the sand at San Onofre State Beach next to the famed Trestles surf spot. Its name comes from two train trestles that parallel the ocean. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The easiest way to get down to the Trestles surf break at San Onofre State Beach is to bicycle along the trail that leads under the concrete train trestles (rebuilt in 2011) that give the spot its name. In 1963, Trestles was mentioned in ¿Surfin¿ USA,¿ the Beach Boys song that became an anthem for a suddenly surf-obsessed generation. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Life is slow and easy for surfers who gather at Trestles. It would be the first surf spot to be listed as a historic site, state officials said. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Local surfer Jeff Quam arrives for a day of surfing at Trestles. To wave riders, it represents seven of the primo surf breaks in the world. To Marines, the middle section of the 2.25-mile stretch of beach is an ideal location to teach grunts how to fight their away from ship to shore and inland. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

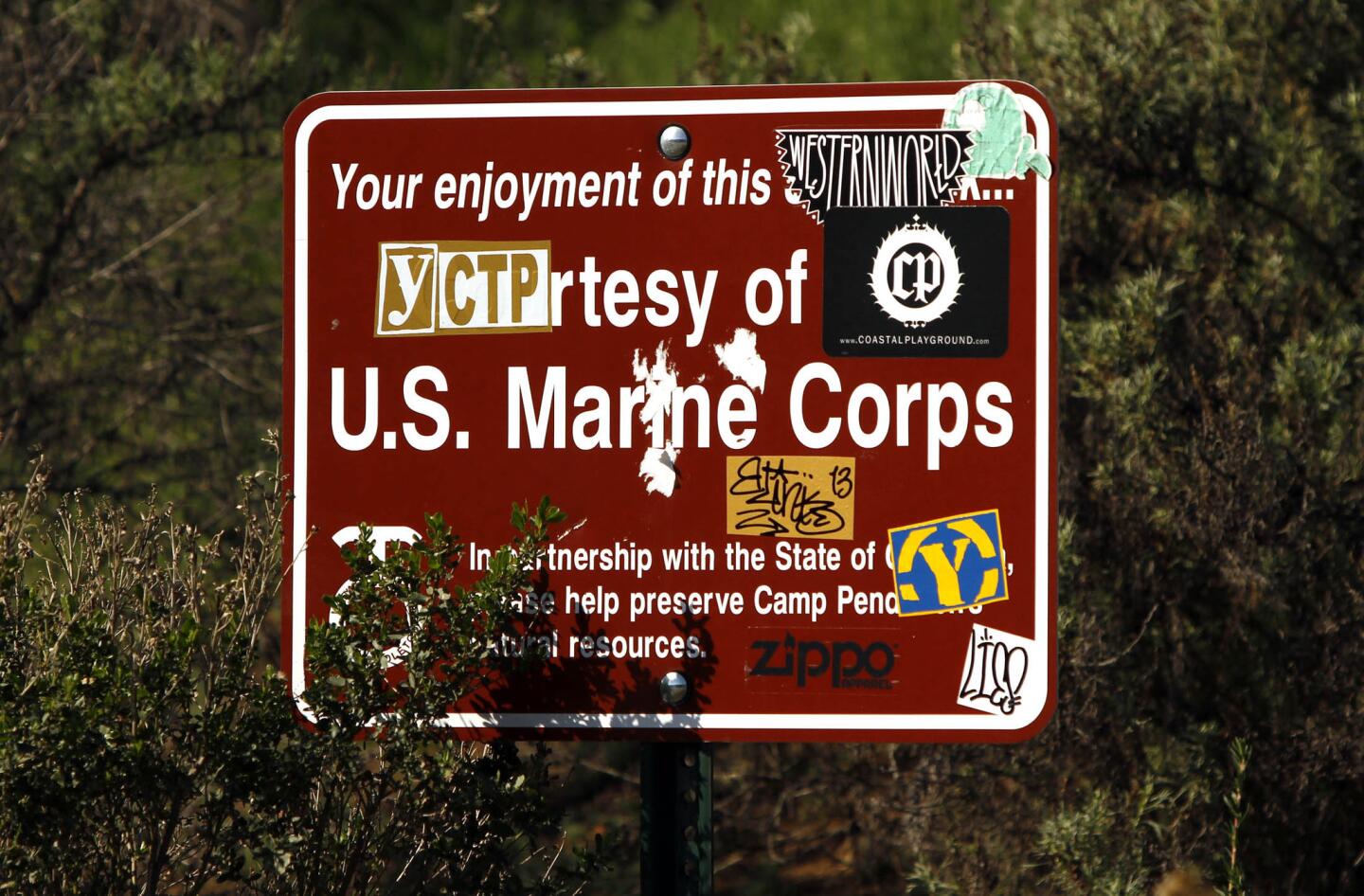

Signs posted along the trail to San Onofre State Beach and the Trestles surf break are nearly obscured by stickers, but they’re still a friendly reminder that public use of the area is courtesy of the Marine Corps. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Surfers warm themselves by a roaring fire at San Onofre State Beach, south of Trestles. With the San Clemente-based Surfrider Foundation in the lead, surfers petitioned to have Trestles listed on the National Register of Historic Places, for its role in the rise of ¿surf culture.¿ (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Surfers gather around a fire pit south of Trestles. Despite opposition from the Marine Corps and the Navy, the State Historical Resources Commission voted unanimously Feb. 8 to forward a recommendation to Washington that Trestles be listed as a historic site. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

A surfer walks on wet sand south of the famed break. Much of the dispute over Trestles involves whether it can be considered Southern California¿s preeminent surf spot ¿ or whether that distinction belongs to Huntington Beach, Santa Cruz or perhaps Blacks Beach in La Jolla. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)